Introduction

India’s urban landscape is undergoing a steady transition. The rapid expansion of cities is leading to challenges such as higher population density, traffic congestion, and rising demand for efficient mobility. These pressures are stretching existing transport networks to their limits and outlining the need for sustainable, high-capacity transit systems that can meet the mobility needs of a growing urban population. While the Government of India and state authorities have played a critical role in the expansion of metro rail, suburban rail, and high-speed corridors, the sheer scale of investment required far exceeds the fiscal capacity of the public sector. According to estimates, India’s urban transport sector will require trillions of rupees in funding over the coming decades to keep pace with demand.

Against this backdrop, Public-Private Partnerships (PPPs) have emerged as a potential solution to bridge the financing and operational gaps. A PPP in rail transit allows the government to use private capital, technical expertise, and efficiency while retaining oversight of strategic public assets. If we take Global examples, cities such as Hong Kong, London, and Dubai have demonstrated how private sector participation, when structured effectively, can accelerate infrastructure delivery, improve service standards, and unlock innovative financing models such as land value capture and transit-oriented development.

In India, however, PPPs in rail-based transit have witnessed mixed results. The Hyderabad Metro Rail and Delhi Airport Metro Express are successful examples of the PPP model. However, cost overruns, contractual disputes, ridership uncertainties, and regulatory complexities have often hindered their sustainability. This raises a critical question: Is PPP a feasible and scalable model for India’s rail transit development, or should public investment remain the dominant driver?

This article explores the dynamics of PPPs in India’s rail sector and examines their opportunities, limitations, and future potential. By evaluating global best practices alongside domestic experiences, the discussion seeks to highlight whether PPPs can provide a balanced pathway for India’s transit expansion or whether a hybrid, India-specific approach is more viable.

Areas for PPP Implementation in Rail Transit Projects

The rail transit sector presents diverse opportunities for Public–Private Partnership (PPP) models, provided responsibilities and risks are appropriately allocated. While large-scale civil works such as viaducts and tunnels usually require public financing due to their high capital intensity and long gestation, several critical components of rail systems are well-suited for private participation.

1. Rolling Stock Procurement and Maintenance

PPP models are particularly effective in rolling stock supply and lifecycle maintenance. Under such arrangements, the private sector can manufacture, finance, and maintain metro coaches or trainsets. This process can ease the financial burden on public agencies. An effective example is the Mumbai Metro Line 1, where rolling stock was supplied and maintained by CSR Nanjing Puzhen (China) under the PPP concessionaire Reliance Infrastructure.

2. Station Development

Stations are the primary component of railway projects. They require extensive upfront capital. This makes them particularly suitable for PPP participation, as they offer potential for non-fare revenue generation through commercial development. The Indian Railways Station Redevelopment Programme, under which stations like Habibganj (Bhopal) and Gandhinagar Capital were redeveloped, showcases how private entities can integrate retail, hospitality, and office spaces with transport facilities. On the metro front, Hyderabad Metro Rail, developed under a PPP with L&T Metro Rail Hyderabad Ltd., heavily relies on the commercial exploitation of station space to make the project viable. Globally, Hong Kong MTR’s “Rail + Property” model is a classic success story of integrating station development with real estate to sustain rail finances.

3. Operation and Maintenance (O&M) Contracts

Private participation in operations and maintenance helps improve service delivery and efficiency. The Hyderabad Metro, India’s largest PPP metro project, is a prime case where L&T Metro Rail Hyderabad operates the network along with commercial components for 35 years under a concession agreement.

4. Logistics and Freight Terminals

PPP models can be extended to freight infrastructure such as multimodal logistics parks, terminals, and associated warehousing functions. For example, the Multi-Modal Logistics Park (MMLP) Nagpur at Sindi is being developed under the PPP (DBFOT) model at an estimated cost of Rs 673 crore with a 45-year concession. It includes facilities such as warehouses, cold storage, cargo handling, and value-added services

Why PPPs in Railways are Failing in India?

PPPs hold potential to effectively support the expansion and modernisation of India’s rail transit sector; however, their implementation in India’s rail sector has been constrained by multiple challenges.

1. Revenue and Ridership Uncertainty

Rail transit projects, especially metro and suburban systems, face unpredictable ridership levels due to factors like competition from road transport, low fare affordability, and changing travel patterns. Since fares in India are usually regulated by authorities to keep them socially acceptable, private players cannot freely adjust tariffs to recover costs. For example, the Delhi Airport Express Metro was initially developed as a public-private partnership between DMRC and Reliance Infra’s subsidiary, DAMEPL. However, the project became financially unviable when passenger traffic fell far short of projections, leading to disputes and the eventual takeover of operations by DMRC. This case highlights how demand risk remains the single largest deterrent for private investment in rail transit projects.

2. High Capital Intensity and Long Gestation

Rail infrastructure requires huge upfront capital expenditure in land, tunnels, viaducts, and rolling stock, with returns spread over decades. Unlike toll roads or airports, rail projects have longer payback periods and relatively lower financial returns. This discourages private players who prefer quicker, visible returns on investment. Moreover, financing costs in India are relatively high.

3. Policy and Regulatory Risks

The frequent changes in project scope, approval delays, or shifting policy priorities create uncertainty. Lack of a uniform national PPP framework for metro and railways means contracts are often customised, which increases negotiation time and legal complexity. For instance, land acquisition delays have frequently stalled station redevelopment projects and directly impacted private investors’ timelines and returns. The delay in the execution of projects increases the overall cost of the project. The absence of strong dispute resolution mechanisms adds to the perception of regulatory risk.

4. Contractual and Risk-Sharing Imbalances

PPP projects often suffer from poorly structured concession agreements that place disproportionate risks on private entities while limiting their flexibility in revenue generation. For instance, if land monetisation rights or commercial space development are delayed by public agencies, private players still bear the financial losses. In many cases, the government retained control over key decisions (like fare revision), but did not share risks equally, leading to litigation and early contract termination.

- Delhi Airport Express Metro (DAMEPL – Reliance Infra and DMRC): In the case of the Delhi Airport Express Metro, fare revision was under the jurisdiction of the Fare Fixation Committee (FFC) and not within the control of the private concessionaire, DAMEPL (Reliance Infra). The fares were kept low to maintain affordability, but the ridership revenues were insufficient to cover costs. At the same time, DAMEPL had to bear the operational and financial risks. The mismatch in risk allocation led to financial losses, disputes, and eventual takeover by DMRC in 2013.

- Mumbai Metro Line 1 (Reliance Infra and MMRDA): Reliance Infra (Mumbai Metro One Pvt Ltd) sought to increase fares, and the reason behind this was higher operational costs and lower ridership. However, fare regulation remained with MMRDA and the Fare Fixation Committee. This led to prolonged legal disputes over fare-setting powers, undermining the financial sustainability of the project

- Hyderabad Metro Rail (L&T Metro Rail Hyderabad Ltd.): The Hyderabad Metro Rail, often cited as the world’s largest PPP in urban transit, is also facing similar challenges. The project has been incurring sustained financial losses, with revenues falling far short of projections, particularly after the pandemic. Larsen & Toubro, which holds a majority stake through L&T Metro Rail (Hyderabad) Ltd., has expressed interest in reducing its exposure by divesting up to 90% of its equity stake, either to the Government of Telangana or to the Government of India through an SPV mechanism. This situation highlights the difficulties private players face in recovering investments and discourages further PPP participation in large-scale railway projects.

5. Institutional Capacity Constraints

Many public agencies lack the technical and legal expertise to design, negotiate, and monitor complex PPP contracts. This results in ambiguities in project agreements, weak enforcement of performance standards, and inadequate mechanisms for mid-course corrections. International investors, in particular, are wary of Indian projects because of these governance gaps.

- A primary example of this is the Indian Railways’ Station Redevelopment Programme. Several high-profile stations, including New Delhi, Chandigarh, and Pune, initially faced limited interest from developers due to unclear risk allocation, unrealistic revenue assumptions, and regulatory uncertainties. By the time the Request for Qualification (RFQ) bids opened in February 2021, the list of contenders had narrowed to nine firms both domestic and international including Adani Railways Transport, Anchorage Infrastructure Investments Holdings, Arabian Construction Company, BIF IV India Infrastructure Holding (DIFC), Elpis Ventures, GMR Highways, ISQ Asia Infrastructure Investments, Kalpataru Power Transmission, and Omaxe. The limited participation highlights how insufficient institutional readiness and complex contractual frameworks can deter even experienced investors from engaging in large-scale urban transport PPPs.

6. Limited Non-Fare Revenue Opportunities

Globally, successful PPP rail projects rely heavily on non-fare revenue streams such as real estate development, advertising, and retail. In India, regulatory hurdles, land acquisition challenges, and bureaucratic approvals often restrict the commercial exploitation of station areas. Hyderabad Metro attempted to use real estate as a financial lever, but delays in approvals and market conditions limited returns, putting additional pressure on farebox recovery.

7. Macroeconomic and Financing Risks

Private players also face risks from currency fluctuations, inflation, and rising interest rates, which affect project financing. Since many components (signalling, rolling stock parts) are imported, exchange rate volatility increases costs. Additionally, Indian banks remain cautious in funding large PPP metro projects due to past cases of stress and defaults. This limits access to affordable financing for private concessionaires.

8. Reputation and Political Risks

Public transport is politically sensitive. Any attempt by private operators to raise fares or cut services for financial viability often faces resistance from governments and the public. This reputational and political risk discourages private firms from making long-term commitments in passenger-centric projects, unlike freight or logistics PPPs, which are relatively less sensitive.

Global Examples in Rail PPPs

Public-Private Partnerships in rail transit have been implemented successfully in several countries, which can offer valuable lessons for India. Globally, the key to successful PPPs lies in clear risk allocation, diversified revenue streams, strong institutional oversight, and innovative financing mechanisms.

- Hong Kong’s Rail + Property Model: A Global Benchmark

Hong Kong’s Mass Transit Railway (MTR) is often referred to as the gold standard for rail Public-Private Partnerships (PPPs) due to its innovative Rail + Property (R+P) model. The MTR Corporation (MTRC) integrates rail operations with property development around stations, creating a self-sustaining revenue model that reduces reliance on government subsidies.

Under this development-based Land Value Capture mechanism, MTRC is granted exclusive development rights for master planning, construction, and management of residential, commercial, and mixed-use projects around its stations. Through this approach, MTRC generates substantial revenues from real estate sales, property leasing, station retail, and consultancy services, in addition to farebox income. This model demonstrates how strategic integration of transit infrastructure with property development can enhance financial sustainability, attract private participation, and enable continuous investment in service quality and network expansion.

Positive profit performance: As of mid-2025, MTR Corporation has a substantial property development portfolio, amounting to around 13 million square meters of floor area across half of its 87 stations, which ensures a steady revenue stream to finance both operations and network expansion. In 2024, MTR reported revenues of HK$60 billion (approx. USD 7.6 billion) and a net profit of HK$15.8 billion. MTR reported HK$5.5 billion in profit from property development in the first half of 2025, a substantial increase over the same period in 2024.

Funding the Future: This property income remains a key part of MTR’s strategy for funding future railway development in Hong Kong. In mid-2025, MTR announced major new investments, including the Northern Link, worth a projected HK$140 billion.

This case illustrates how the integration of transit development with land and property management can ensure long-term financial sustainability, attract private capital, and deliver continuous improvements in service quality.

Bangkok BTS Skytrain: A Pioneering Yet Evolving PPP Model

The Bangkok BTS Skytrain, launched in 1999, stands as a pioneering example of a large-scale urban rail public-private partnership (PPP) in Southeast Asia. It was among the first major metro projects in the world to be entirely financed by the private sector under a Build-Operate-Transfer (BOT) model. The Thai government awarded a 30-year concession to the Bangkok Mass Transit System Public Company Limited (BTSC), which was responsible for financing, constructing, and operating the system.

At its inception, the project was considered successful, with BTSC raising capital through a mix of domestic and international loans, private equity, and bond issues. Unlike many global metro systems, the BTS Skytrain was launched without direct government subsidies for construction.

However, the project also exposed key risks in PPP ventures. In its early years, passenger ridership fell well below projections, which had put financial strain on BTSC and forced a debt restructuring process in the mid-2000s. To address this, the Thai government and Bangkok Metropolitan Administration (BMA) later took a more active role in system expansion and integration, while BTSC retained rights to operate the core system and benefit from non-fare revenues such as advertising, retail concessions, and real estate ventures.

Today, after more than two decades, the BTS Skytrain has become the backbone of Bangkok’s urban mobility. It carries more than 750,000 passengers daily (pre-pandemic levels). Its financial model has evolved into a hybrid approach, with the state now co-financing expansions while BTSC continues to manage operations. The long-term concession, extended to 2042, gives BTSC operational stability and the ability to generate revenues from farebox and non-farebox sources.

The BTS Skytrain case demonstrates both the promise and pitfalls of private-led PPPs in urban transit. The BTS Skytrain cannot be labelled a full success or a failure it is a mixed case. On one hand, it demonstrated that large-scale rail systems could be delivered by the private sector without upfront government funding. On the other hand, it highlighted the risks of over-optimistic demand forecasts, limited fare flexibility, and weak multimodal integration.

The eventual shift to a hybrid PPP approach reflects the reality that urban transport requires sustained government involvement to ensure long-term financial and social viability. Importantly, the BTS model is still evolving, with ongoing renegotiations of contracts, network expansions supported by the state, and adjustments in its business model to balance financial performance with public accessibility.

From Expectations to Reality: PPP Performance in India’s Metro and Rail Projects

India’s implementation of Public-Private Partnerships (PPPs) in the Metro and Railway sectors presents a mixed picture. The Indian government has taken multiple initiatives to promote PPPs in India’s rail transit sector.

Active PPPs in Metro Rail

- Policy push: India’s Metro Rail Policy of 2017 strongly encourages private participation for metro projects to be eligible for central government assistance. This includes various models like those leveraging Viability Gap Funding (VGF) from the central government, equity sharing (50:50), and full private funding models.

- Potential areas for PPP: Despite the issues, opportunities exist for private players in areas like operations and maintenance (O&M), development of Automated Fare Collection (AFC) systems, and creating infrastructure for last-mile connectivity.

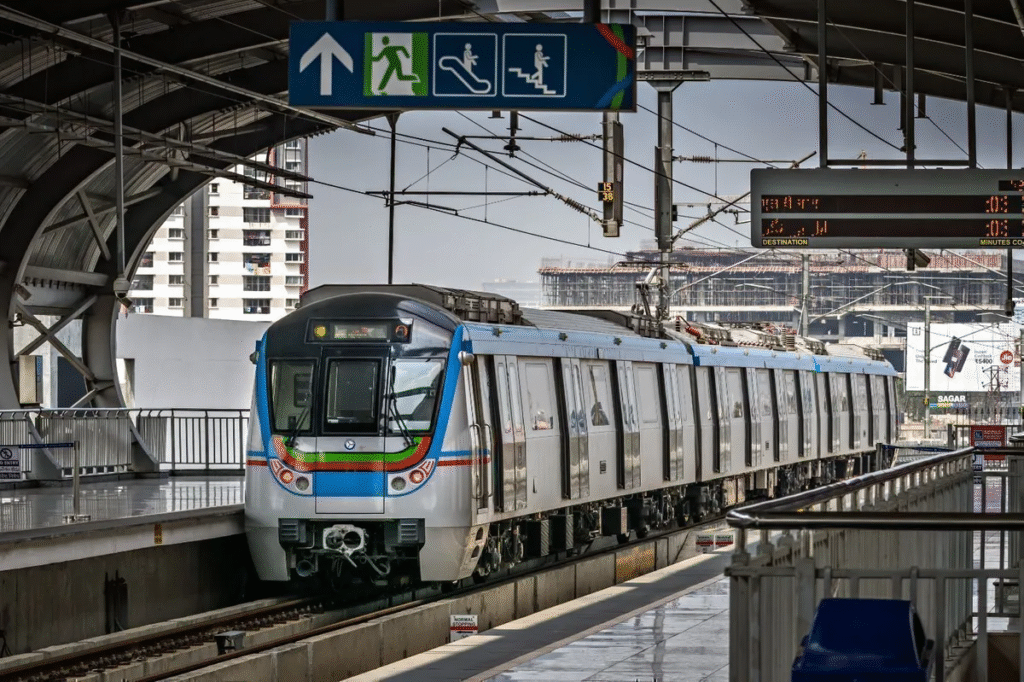

1. Hyderabad Metro

The Hyderabad Metro is the world’s largest metro project developed as a Public-Private Partnership (PPP), based on a Design-Build-Finance-Operate-Transfer (DBFOT) model. L&T Metro Rail (Hyderabad) Limited (L&TMRHL), a subsidiary of L&T, was established to implement the project. The company signed a concession agreement with the government in 2010 to finance, build, operate, and maintain the metro for a 35-year concession period (five years for construction and 30 years for operation).

Operations and Maintenance (O&M): L&TMRHL outsourced the day-to-day O&M to the French transport operator Keolis.

Financial distress: L&T has incurred massive financial losses, which reached ₹625.88 crore in FY 2024–25. In September 2025, L&T announced its intention to exit the project.

The model’s reliance on projected ridership and commercial revenues proved unsustainable for the private partner. This has led to a major shift in India, where metro projects are now moving toward hybrid or gross-cost O&M contracts that better share risk and avoid the financial burdens seen in comprehensive PPPs.

2. Pune Metro Line 3

The 23.3-kilometre Pune Metro Line 3 is being implemented through a Public-Private Partnership (PPP), but unlike the comprehensive Hyderabad Metro model, it has a more balanced and unbundled structure. The project is led by the Pune Metropolitan Region Development Authority (PMRDA) in a partnership with a consortium of the Tata Group and Siemens.

- Concessionaire: A special-purpose vehicle (SPV) named Pune IT City Metro Rail (PITCMRL) was set up by a consortium of TRIL Urban Transport Private Limited (a Tata Group company) and Siemens Project Ventures GmbH. The concession agreement is for 35 years.

- Funding: The project is estimated to cost over ₹8,100 crore, and it uses Viability Gap Funding (VGF) to mitigate risk. The central government will contribute up to 20% of the initial project cost, with the Maharashtra state government providing the rest of the VGF.

- Operational partnership (O&M): The concessionaire, PITCMRL, has awarded a separate 10-year Operations and Maintenance (O&M) contract to the French multinational transport operator Keolis.

The Pune Metro Line 3 model is designed to deliver a high-quality public service while minimising the risk of financial distress for the private partner. Unlike Hyderabad Metro, where the private player L&T had to bear significant demand and revenue risks, Pune’s model includes VGF from the government. This financial support reduces the long-term demand risk for the private partner.

PPP in Indian Railways

The Indian railway sector is actively exploring Public-Private Partnerships (PPPs) as a key strategy to bridge funding gaps, modernise infrastructure, and enhance operational efficiency.

Station Redevelopment Programme

The Government of India launched the station redevelopment programme. This programme aims to turn the railway stations into modern, world-class transport hubs that offer a superior travel experience. The programme is implemented mainly under the Amrit Bharat Station Scheme (ABSS). As of March 2025, the Ministry of Railways has identified 15 stations, out of a total of 1,337, for redevelopment through the public-private partnership (PPP) model under the ABSS.

Performance of PPP in Station Redevelopment

Rani Kamalapati Station (Bhopal) is considered the most successful station redevelopment project completed under the PPP model. However, the model has not proven to be sustainable in all cases. For instance, projects at New Delhi Railway Station and Chhatrapati Shivaji Maharaj Terminus (CSMT, Mumbai) were initially planned as PPPs, but high bid prices and limited interest from private investors led to these projects being reverted to the EPC (Engineering, Procurement, and Construction) model.

Opportunities for EPC Contractors

According to a report by ICRA published on 23 December 2024, engineering, procurement, and construction (EPC) companies are expected to see business opportunities worth approximately ₹30,000 crore over the next two years in railway station redevelopment projects.

New PPP Policy Framework for Railways to Make the Model Sustainable

Indian Railways has formulated a new Public-Private Partnership (PPP) policy, which is expected to receive Union Cabinet approval soon. It will replace the Participative Policy for Rail Connectivity and Capacity Augmentation Projects, 2012. The updated PPP framework plans to bring approximately 50 railway projects under private sector participation, compared to 17 projects under the previous policy. The policy will focus on commercially viable corridors, which include port connections and mineral transport routes, which are expected to generate strong returns and attract further private investment.

- Working of the New PPP Framework: The revised PPP framework allows private investors to recoup their expenditures by imposing tariffs on freight operations along the infrastructure they develop. Indian Railways will, in parallel, receive a fixed payment and a portion of the revenue generated

This initiative follows the suggestions of a recent Standing Committee on Railways, which recommended:

- Encouraging the use of modern technologies in coach manufacturing through private sector participation.

- Expanding the production of train coaches, wagons, and containers using the PPP model.

- Copying successful PPP station projects, like Rani Kamalpati Station, at other stations across India.

Over the past three years, Indian Railways has earned only modest profits, mainly due to lower passenger revenue and heavy dependence on freight. The government aims to fill funding gaps, improve efficiency, and reduce the financial load on the public sector by bringing in private investment and expertise.

Conclusion

India’s rail transit sector is undergoing major changes and needs ongoing investment to expand infrastructure and improve efficiency for both passenger and freight services. The Public-Private Partnership (PPP) model can support this process by allowing private companies to bring in capital, technical expertise, and operational efficiency, which can reduce the financial burden on the government.

Global examples, like Hong Kong’s Mass Transit Railway, show that PPPs can help generate stable revenues and maintain high service standards. In India, however, PPPs in railway and metro projects have had limited success due to gaps in institutional capacity and uneven sharing of risks between public and private partners.

To make PPPs work on a larger scale in India, there is a need for a clear framework that provides regulatory support, financial mechanisms, and fair risk-sharing, allowing private companies to participate effectively in large infrastructure projects.